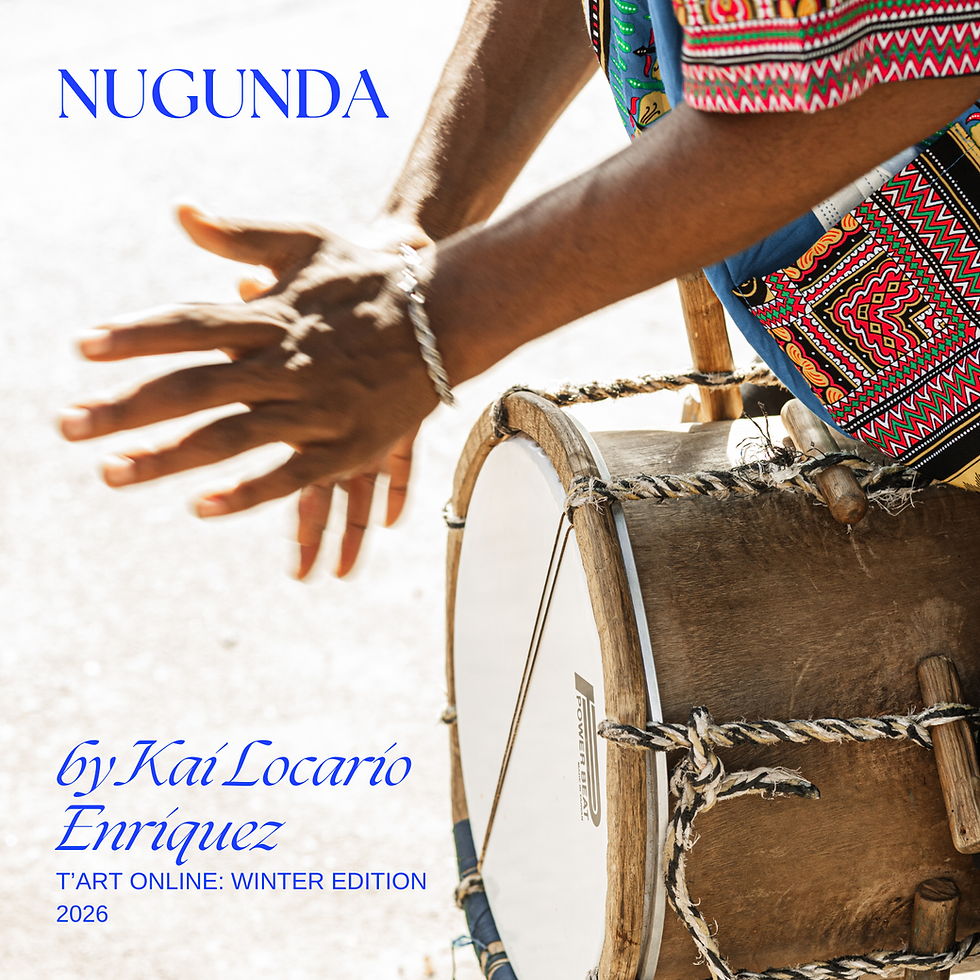

Nugunda by Kai Locario Enriquez

- Finn Brown

- 1 day ago

- 8 min read

Whenever I expressed an interest in learning Garifuna as a child, my parents dissuaded me by saying, "It's too hard to learn. Just learn Spanish instead."

It's an Arawakan language that was created on St. Vincent during the 1600s when Africans were shipwrecked on the island. The Indigenous groups — Kalinago and Arawak — adopted the marooned Africans into their culture.

I had spent hours standing with aching legs in the kitchen as I helped my mother knead the masa for panades. When making garnaches, my body knew to lean back so I wouldn't be burned by any popping oil. I knew the difference between the Primero and Segundo drums, about the significance of the black, white, and yellow colors of our flag. I could answer any questions about Belize, but expressing any of that in Garifuna was robbed from me.

I was the only child given a Garifuna middle name; all of my siblings had religious ones. The cement that had been poured over our lineage still oozed and hardened over my body. I tried to form cracks by prodding around, asking my relatives about what our names were like before the Europeans replaced ours with theirs. I wanted my inquiries about who we believed in before the Abrahamic God to create a small dam, a bit of reprieve, but I was met with snaps and swats.

"We don't worship the devil anymore," my aunt had hissed, "and Garifuna names are too hard for Americans to pronounce."

Devil. That word resounded through my brain, like the church bells calling each hour. I desperately wanted to shake the colonizers of our culture for shackling our history to taboo. I wanted to puncture the hot air balloon called the American Dream in front of my relatives' eyes. I wanted to scream about how they were casting out our ancestors to cradle a colonizer's belief about our culture. It seemed like all attempts to connect with Garifuna history were methodically ruined by my relatives.

Americans were no better at accepting our culture. Upon hearing my parents speak, every Uber driver, grocer, or person we interacted with asked, "Where are you guys from?" Each time we answered, we gained a look of confusion, a request to say our ethnicity again.

Almost everyone continued with, "I've never heard of that before. What is that?"

Most of the time, it looked like our answer disappointed them. That disappointment seeped into my brain and my bloodstream, morphing into shame and jealousy. I wanted something cooler, something I could brag about. I yearned to be like my friends who knew Spanish, who could go back to their parents' countries whenever they wanted, and feel like they were a part of it. For me, there was always a faint dissonance. It felt like my hands were reaching out and only being met with frigid air. I was just a puppet for my culture, never the one pulling the strings.

In my sophomore year of university, I had been assigned a research project about culture and ethnicity. It was an opportunity to salvage my connection with both the Garifuna culture and language. I ached to excavate the disappointment from my bones. I needed the phantoms of my being to solidify and embrace me. I wanted to feel proud of my culture and accept it wholeheartedly.

My grandmother had asked, "Well, what would you like to know?" when I sat her down for questioning.

"Everything," I replied. "You're the only one that's fluent in Garifuna. How did you keep it? Did you try to pass it down to your children?"

"Yes. They all knew it, but when we moved to the States, they didn't need it. It was harder to find work back then if you had a thick accent. I didn't need to worry about that because I couldn't work." She shifted in her chair and continued, "I only spoke to them in Garifuna at home, and as time passed on, they just started responding to me in English. It's been years since I've heard any of them speak in Garifuna."

I typed her response into my computer, trying my best to blink tears from my eyes. To survive, my parents and their siblings had to scrape their language from the grooves of their tracheae. They were forced to ingest a parasite that would slowly make them a husk of their culture.

"Why?" She asked. "Do you want to learn?"

My head snapped up to look at her. Desperation saturated my mouth as I answered, "Yes, please."

A smile lit up my grandmother's face. She fixed the bandana she had tied over her white hair and leaned over to hold my hand. "Nebari, keimoun."

I could only reply with, "What?"

"My grandchild, let's go," she translated.

She taught me how to say the basics: hello, how are you, my name is…, I love you, and I'm proud of you. We slowly started greeting each other that way, and each time, her face lit up brighter and brighter. Her eyes shone whenever I entered the room. It brought my grandmother — nagut — and I closer than ever before. She started telling me everything about Belize from the 1920s through the 1960s before my relatives immigrated to the States. She would laugh as she recounted stories of her parents and husband, who had all passed away decades prior.

Sitting in her room with her felt like we were sitting with all of the Garifuna people who had come before us. Their warm hands on my back, their laughter filling the room alongside her. Warmth filled my chest with each word that left her lips, each translation she gave whenever she quoted her loved ones. The phantom I had chased my entire childhood had become tangible. The connection I longed for embraced me with reverence.

Relief and love ejected the disappointment from my veins. I knew that assimilation would always affect me, but at least I had nagut who could bestow all her wisdom upon me. At least I had finally found a footing in my own culture. I was the puppeteer, slowly mastering the language. I could slowly untie the string of fate my parents had knotted and ensure Garifuna wouldn't die with my generation.

Futility bubbled in my chest when I saw nagut lying in her coffin almost a year later.

My mother had said, "There's no need to cry. She's happy and loved in Heaven by God."

My first thought was about her husband, who she talked about honey-like softness. I wondered if she was back in her parents' arms, or with the daughters who had passed before her. I knew any rebuttal wasn't allowed. Mortality was the progenitor to all my diseases — the slow death of the Garifuna language, the agonizing death of our culture in favour of religion, the complex I had because of it, and the grief I held for losing nagut. They were enmeshed in white masks of colonization and the Anglo-Saxon brush of homogeneity.

Trying to remember all the Garifuna nagut had taught me, but not being able to speak it with her, felt like lava had been poured in my mouth. Tears raced down my cheeks as my tongue traversed the scalding liquid to form words. What felt natural to my ancestors felt foreign in my own mouth without her guiding me.

"Buiti binafi. Ida biangi?" I whispered in my cold bedroom. (Good morning. How are you?)

There was no answer. I responded to myself, "Úwadigati. Agia bugía?" (I'm fine. And you?)

Fresh tears burned my eyes as I clutched my chest. There was no remedy for the pain. There was no balm I could place over my heart to make up for the loss. There would be no more answers, no more dialogue, no more connection. The room had lost all laughter and happiness; it had been replaced with my wailing and tears.

Shame flared up again. I was hit with the realization I would never be as fluent in Garifuna as nagut was. I would never grasp or comprehend all the nuances of the culture coursing through my veins, only of the one forced upon my lineage. The same one that worked so hard to erase all that my ancestors sacrificed to preserve and maintain. I had Sisyphus's destiny. I was always on the precipice of grasping it all before I was shot back down with the reality of knowing I could only occupy a shell of language, the husk of ghosts' whispers.

My relatives would say, "Think about what she would have wanted. She wouldn't want to see you this sad. Don't force yourself to learn Garifuna."

Vehemence shot through my entire being. The same people who refused to reply to her in Garifuna or listen to her stories of the past were the same people continuing to dissuade me. I became livid with each word that left their lips. All she had wanted was someone she could share and teach with, and I had been the only person to bring her wants into fruition. Now that she was gone, everyone felt like they had the right to speak for her, when no one had listened to her when she was alive.

On one hand, I wanted to be empathetic and understand that they were forced to let go of their culture to survive in a new country. I was cognizant of how easier it must have been to let go of the divergence than cling to what they knew could not exist simultaneously. On the flip side, I knew that wasn't my plight. I didn't have to barter parts of myself to make ends meet. My ultimate goal was salvaging all I could from the wreckage and reconnecting the almost obliterated tie.

I had to ameliorate the agony in my chest to continue tending to the space nagut created for me. I fought back against English garroting my Garifuna by purchasing textbooks and workbooks. I replayed all the recordings I had taken of nagut to crystallize and eject the lava traversing my mouth. Excitement slowly permeated my senses each time I pronounced a word or conjugated a verb correctly, even when silence was still my only reply.

I could still learn new words and build sentences, no matter how clunky they sounded. I didn't want to further the disrespect my ancestors faced by letting despair and colonization discourage me. Daydreams took flight from the basin of growth. I imagined Garifuna being taught in universities, Hollywood films or TV shows having Garifuna characters in them, and a book fully in Garifuna listed as a New York Times Bestseller. There were so many ways to grow, especially in shedding the belief that any ties to the past were akin to Satan or that preserving our language wasn't of the utmost importance. I made a vow to never allow anything to power wash Garifuna from my psyche or lips.

People are still so confused and ask me to repeat myself when I say I'm Garifuna, but shame no longer flashes through me. I feel that same spark of joy nagut did when she taught me our language. I can picture her beaming at me and encouraging me to speak more, to speak louder, and to speak with conviction. Each time I speak about my culture, I embodying my middle name, Nugunda, meaning my joy.

Kai Locario Enriquez (they/them) is Garífuna writer of mainly pose and poetry based in Los Angeles. They have a BA in Narrative Studies from the University of Southern California, where they were also trained in playwriting, screenwriting, and songwriting. The common themes throughout their work are the isolating feeling of growing up queer and trans, the discombobulating web of grief, the small but significant moments of happiness, and being the child of Central American immigrant parents. Their wish is to become a multi-lingual multimedia artist.

Comments